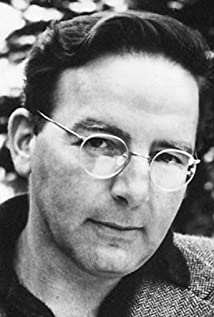

Cy Endfield

The son of a struggling businessman, Cy Endfield--born Cyril Raker Endfield--worked hard to be admitted to Yale University in 1933. While completing his education he became enamored with progressive theatre and appeared in a New Haven production of a minor Russian play in 1934. He was also profoundly influenced by such friends as writer Paul Jarrico, who was in Hollywood and who advocated liberal and leftist views. For several years Endfield worked as a director and choreographer with avant-garde theatre companies in and around New York and Montreal. He led his own repertory company of amateur players in performances of musicals and satirical revue at resorts in the Catskills.

Endfield had another string to his bow, having established a not inconsiderable reputation as master of the art of micro magic, particularly card tricks. In a circuitous way this brought him to Hollywood in 1940. There have been conflicting stories as to how he came to the attention of Orson Welles, who was known to have a long-standing fascination with magic. Endfield first met Welles in a magic shop, but it was his producer and business manager Jack Moss, himself a magician, who hired Endfield for the Mercury Theatre as a "general factotum". Moss wanted to enhance his own skills in order to confound Welles, who had engaged him in the first place as a tutor for performing magic on stage. In return for his expertise, Endfield was permitted to sit in on the making of Journey Into Fear (1943) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), learning valuable lessons in the process. By 1942 he was ready with his first film, a 15-minute-long documentary about the danger of rampant capitalism, entitled Inflation (1943). The witty little piece was a subtle attack on corporate greed and corruption and featured well-known actor Edward Arnold as a devil in businessman garb. An outspoken social critic, who had flirted briefly with the Young Communist League back in his days at Yale, Endfield was from the outset on a collision course with the establishment. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce banned his film as "excessively anti-capitalist" and kept it from public view for half a century.

Following wartime service, Endfield wrote several scripts for radio and television. He directed a number of short documentaries for MGM in 1946, and followed this with his motion picture debut, Gentleman Joe Palooka (1946), based on a popular comic strip character, shot in eight days at "Poverty Row" studio Monogram Pictures. He also directed a B-mystery, The Argyle Secrets (1948), from his own earlier radio play, followed by one of the better entries in the "Tarzan" series, Tarzan's Savage Fury (1952). Unfortunately, the picture did poorly at the box office. The reason for this, producer, Sol Lesser suggested later, was because Lex Barker (as "Tarzan") had been given too many lines to speak and "nearly talked himself to death". It was not until Endfield's harrowing indictment of mob rule, The Sound of Fury (1950), that he "arrived" as a director of note. That same year he helmed another independently produced minor masterpiece (on a budget of $500,000), the stylish and moody film noir The Underworld Story (1950). In this scathing attack on unscrupulous journalism, with the lead character being inherently unsympathetic, Endfield elicited one of the finest performances of his career from Dan Duryea.

The ideas and sentiments expressed in these films were ill-timed, in that they drew the attention of HUAC--The House Un-American Activities Committee, which was tasked with rooting out Communists and other "subversives" in the entertainment industry--which particularly denounced "Sound of Fury" as being un-American. Though never a card-carrying member of the Communist Party, Endfield found himself "named" as a sympathizer. Preferring to leave the country rather than inform on others to the FBI, he settled his affairs and left for a new career in Britain in December 1951. To avoid problems with distribution in the US, for the first few years he worked under pseudonyms (such as "Hugh Raker") and on two occasions allowed a friend of his, director Charles de la Tour, to act as a 'front'. He used his own name again for the offbeat action film Hell Drivers (1957). This uncompromisingly tough working-class melodrama featured Stanley Baker, with whom Endfield formed a production company in the 1960s. Baker eventually starred in six of Endfield's films, including the routinely scripted drama Sea Fury (1958) about tugboat sailors and the rather over-the-top Sands of the Kalahari (1965). From the late 1950's, Endfield became also increasingly involved in turning out television commercials. He also worked in the theatre again, directing Neil Simon's play "Come Blow Your Horn" at the West End.

Certainly the most visually impressive and successful of Endfield's films is Zulu (1964), the epic story of the Battle of Rorke's Drift in 1879 between a small contingent of British troops and a vastly superior force of Zulu tribesmen. The original story was penned by military writer John Prebble and Endfield had written the screenplay as early as 1959. After several abortive attempts, he was able to parlay his way into the offices of producer Joseph E. Levine in Rome and was finally given the go-ahead. Enhanced by John Barry's rousing score, "Zulu" is a supremely well-choreographed "battle ballet"--the battle scenes constitute well over half the screen time), with numerous lateral tracking shots of the main protagonists, which effectively draw the audience into the heart of the action. The social element is concerned with British imperialism and class structure, as two officers from different backgrounds are forced to pull together in order to stay alive. As the supercilious upper-crust Lt. Bromhead, Michael Caine, then relatively unknown, began on his path to fame with an excellent performance, alongside Stanley Baker. Historical incongruities apart, "Zulu" succeeded as pure spectacle, much in the same way as the big-budget Hollywood epics of the same period.

Endfield lost interest in filmmaking after shooting the anti-war movie Universal Soldier (1971). This was in part due to the fact that most of his films had failed to make much money. After the death of his friend Stanley Baker in 1976, Endfield devoted himself to his "technical period". He manufactured a gold-and-silver chess set as commemoration for a famous match between grand masters Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky in 1972 (only 100 were ever produced). In 1980 he invented the first pocket word processing system, the "MicroWriter", which had re-chargeable batteries and a 14-character LCD display.

In 1955 Endfield had co-authored a very successful book, "Cy Endfield's Entertaining Card Magic" (with Lewis Ganson), which had been well-received by amateur and professional magicians alike. In fact, one of his admirers, and occasional collaborators, was the famous micro magician Dai Vernon. Many of the sleight-of-hand routines in the book were developed by Endfield himself and related to the reader in a manner befitting a consummate storyteller. Endfield's passion for performing magic remained with him to the end. The multi-talented polymath resided in Britain until his death in April 1995.